RMD Strategies to Help Ease Your Tax Burden

Note: Due to the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, required minimum distributions (RMDs) for IRAs are waived for 2020.

Many people who save money in traditional 401(k)s, Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), or other tax-deferred investment vehicles do so assuming their income-tax rate in retirement will be lower than that of their working years. The whole premise behind tax deferral is we know we’re going to have to pay income tax on this money eventually. We just want it to be less in retirement than what we’d pay during our working years.

However, it’s not unusual for retirees to find themselves in the same or an even higher tax bracket in retirement. How so? “Many people tap accumulated wealth outside their IRAs,” says Kathy Cashatt, a Schwab senior financial planner in Phoenix. “When you add that income to Social Security and the required minimum distributions (RMDs) you can land in an unexpectedly high tax bracket.” Keep in mind with the recent passage of the SECURE Act, the age for the onset of RMDs has changed from 70½ to 72 for retirees turning 70½ after December 31, 2019. Retirees who turned 70½ before 2020 will still have the same RMD requirements.

Fortunately, a number of strategies can help reduce the impact of RMDs.

How is the RMD calculated?

The IRS calculates RMDs by taking the sum total of all your tax-deferred retirement accounts at the end of each year and dividing it by a number based on life expectancy and other factors. The denominator gets smaller and smaller as your age increases, meaning your distributions get larger and larger. For example, the denominator starts at 27.4 for those age 70½, or about $3,650 for every $100,000 in savings, and declines to a low of 1.9 for those age 115 or older, or about $52,630 for every $100,000 in savings (see chart below).

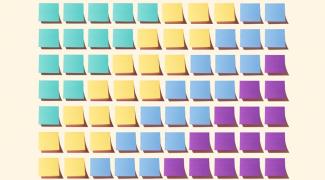

RMD amounts change over time

Required minimum distributions (RMDs) from tax-deferred retirement accounts increase as you age.

Source: IRS.gov.

Many IRA custodians will notify account holders of their RMDs each January (though the IRS holds the account owner ultimately responsible for getting the calculations right). Schwab offers an online calculator to help investors estimate annual distributions. The cost of miscalculating or failing to withdraw the full amount is steep: The IRS charges a 50% penalty on any withdrawals required but not taken.

In many ways, the first year of RMDs can be the toughest. That’s because your initial distribution isn’t due until April 1 of the year after you turn 70½ (or 72 if you’re subject to the new rules)—even though your second RMD is due on December 31 of that same year. Two sizable, taxable withdrawals in the same tax year can more easily bump savers into a higher bracket, so it’s often best to take your initial distribution during the first calendar year in which it’s mandated. (Even after that initial hump, IRA holders should remain vigilant, because your remaining balances will continue to fluctuate—and with them your RMDs.)

A step-by-step guide to calculating your RMD

-

Add up all tax-deferred retirement account balances as of 12/31/2020.

-

Find the number that corresponds to the age you will turn in 2021 from the table below.

-

Divide No. 1 by No. 2. This is your required minimum distribution for 2021.

RMD denominator

Source: IRS.gov. If your spouse is the sole beneficiary of your tax-deferred retirement accounts and he or she is more than 10 years younger than you, visit the Required Minimum Distribution Worksheets page of IRS.gov for a worksheet specific to your situation.

When should you begin drawing down your accounts?

Option 1 – begin taking withdrawals at age 59 ½: One approach is to begin withdrawing funds from tax-deferred accounts at age 59½—generally your earliest opportunity without incurring a 10% penalty—although not so much that you edge yourself into a higher tax bracket. This strategy can reduce the overall size of your tax-deferred accounts, and with them your RMDs once you turn 70½ (or 72 if you’re subject to the new rules). Such withdrawals can also help make it possible to defer claiming your Social Security benefit, which increases 8% for every year you wait to collect beyond your full retirement age (up to age 70, after which there is no incremental benefit).

Option 2 – convert your IRA to a Roth IRA: A second strategy is to convert holdings in your traditional IRA to a Roth IRA, which is exempt from RMDs.

There are several situations in which such a conversion may make sense:

-

You believe you’ll be in a higher bracket when you eventually withdraw the money.

-

You want to manage or reduce distributions after age 70½ or 72, depending on when your RMDs begin.

-

You want to leave your heirs an income-tax-free asset, as Roth withdrawals aren’t subject to income tax, assuming you’ve held the account for at least five years.

If you have a sizable income in retirement or don’t need the IRA money for living expenses, a Roth conversion could be a good approach. However, you’ll pay ordinary income tax on the amount distributed from your regular IRA—and it’s to your advantage to pay any income-tax liability from other assets.

That’s because, if you’re under age 59½, tapping IRA funds to pay the tax bill stemming from your Roth conversion will result in a 10% penalty on top of any ordinary income tax. Whereas if you’re over age 59½, using your IRA funds to satisfy your tax bill reduces the amount left to grow tax-free, undercutting the rationale behind your Roth conversion to begin with.

A Roth IRA conversion can be especially advantageous during your initial years of retirement when RMDs haven’t yet kicked in and you’re most likely to be in a lower tax bracket vis-à-vis your working years.

Option 3–make a qualified charitable distribution: Once you reach 70½, a third option to reduce or entirely satisfy your RMDs opens up: a qualified charitable distribution (QCD), in which funds are transferred directly from an IRA to a qualified charitable organization. QCDs count toward RMDs but are not taxable, and an individual, whether married or single, can donate up to $100,000 a year from her or his own IRA—with several important caveats:

-

Your IRA custodian must transfer the funds directly—and only to a 501(c)(3) organization (donor-advised funds aren’t eligible).

-

You can’t claim the QCD as a charitable deduction, though neither does the distribution count as taxable income.

-

A retiree turning 70½ in 2020 can still make a QCD even though the retiree does not have to take an RMD for 2020.

Putting the puzzle together

Given the SECURE Act and The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act it’s best to consult with a certified public accountant or qualified tax advisor who can help you navigate the intricacies of the new tax law.

“From multiple tax-deferred accounts to Social Security to other potential sources of income, there are a number of moving pieces,” Kathy says. “So it’s never too early to start planning.”